My Journey into Academia Part Two

Tuesday, January 28, 2014

1 comments

I have always maintained a strong separation between jIIr -which is my personal blog - and the work I do for my employers. For one time, for one post I'm blurring the lines between my personal publishing platform and work I did for an employer. I previously posted about My Journey into Academia where I discussed why I went from DFIR practitioner to DFIR educator. I'm continuing the journey by discussing the course I designed for Champlain College's Master of Science in Digital Forensic Science (MSDFS) program. My hope is by sharing this information it will be beneficial to those developing DFIR academia curriculum and those going from DFIR practitioner to DFIR educator.

My Journey into Academia post goes into detail about the issue where some academic programs are not preparing their students for a career in the digital forensic and incident response fields. How students coming out of these programs are unable "to analyze and evaluate DFIR problems to come up with solutions." In the words of Eric Huber in his post Ever Get The Feeling You’ve Been Cheated?:

"It’s not just undergraduate programs that are failing to produce good candidates. I have encountered legions of people with Masters Degrees in digital forensics who are “unfit for purpose” for entry level positions much less for positions that require a senior skill level."

As I said before, my choice was simple: to use my expertise and share my insight to improve curriculum; to put together a course to help students in their careers in the DFIR field.

Years ago I went to my first DFIR conference where I met Champlain's MSDFS program director at the time. One of the discussions we had was about the program being put together. A program that was supposed to not only help those looking to break into the field but to benefit those already in the field by covering advanced forensic topics.

Years later when an opportunity presented itself for me to develop the Malware Analysis course for Champlain's MSDFS program I remembered this discussion. I always heard great things about Champlain's programs and it was humbling to be offered this chance. It was even better when I took a look at the MSDFS curriculum. Seeing courses like: Operating System Analysis, Scripting for Digital Forensics, Incident Response and Network Forensics, Mobile Device Analysis, and then adding Malware Analysis to the mix. The curriculum looks solid covering a range of digital forensic topics; a program I could see myself associated with.

For those who don't want to pursue a Master's degree can have access to the same curriculum through their Certificates in Digital Forensic Science option. An option I learned about recently.

How can you reverse malware if you are unable to find it? How can you find malware without identifying what the initial infection vector is? How can you identify the initial infection vector without knowing what artifacts to look for? How can you consistently explore artifacts without a repeatable process to follow? How can you carry out a repeatable process with having the tools to do so? I could go on but this adequately reflects the thought process I went through when developing the curriculum. Basically, the course had to explore malware in the context that a DFIR practitioner will encounter it. To me, the best way to approach building the course was by starting with the course objectives and the following were the ones created (posted with permission):

- Evaluate the malware threat facing organizations and individuals

- Identify different types of malware and describe their capabilities including propagation and persistence mechanisms, payloads and defense strategies

- Categorize the different infection vectors used by malware to propagate

- Examine an operating system to determine if it has been compromised and evaluate the method of compromise

- Use static and dynamic techniques to analyze malware and determine its purpose and method of operation

- Write reports evaluating malware behavior, methods of compromise, purpose and method of operation

After the course objectives were created the next item I took into consideration was the reading materials. One common question people ask when discussing academic courses is what the courses’ textbooks are. I usually have mixed feelings about this question since the required readings always extend beyond textbooks. The Malware Analysis course is no different; the readings include white papers, articles, blogs, reports, and research papers. However, knowing the textbooks does provide a glimpse about a course so the ones I selected (as of the date this post was published) were:

Szor, P. (2005). The Art of Computer Virus Research and Defense. Upper Saddle River: Symantec Press.

Russinovich, M., Soloman, D., & Ionescu, A. (2012). Windows Internals, Part 1 (6th ed.). Redmond: Microsoft Press.

Honig, A, & Sikorski, M. (2012). Practical Malware Analysis: The Hands on Guide to Dissecting Malicious Software. San Francisco: No Starch Press.

Ligh, M., Adair, S., Hartstein, B., & Richard, M. (2011). Malware Analyst’s Cookbook and DVD: Tools and Techniques for Fighting Malicious Code. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing.

I started creating the curriculum after the objectives were all set, the readings were identified, and most of my research was completed (trust me, I did plenty of research). When building out the curriculum its helpful to know what format you want to use. Similar to my collegiate experience (both undergraduate and graduate), I selected the traditional teaching methods for the course such: lectures, readings, discussions, laboratories, and assignments. I made every effort to make sure the weekly material covered by each teaching method tied together as well as the material from each week.

To illustrate how the weekly material ties together I thought it would be useful to discuss one week in the course; the course's second week material which explores anti-forensics and Windows internals. Each week (eight in total) begins with a recorded lecture. The lectures either convey information that is not discussed in the readings - such as a process - or re-enforces the information found in the readings and lab. The week two lecture explores anti-forensics to include: what it is, its strategies, and its techniques to defeat post mortem analysis, live analysis, and executable analysis. When dealing with malware whether on a live system (including memory images), powered down system, or the malware itself it's critical to know and understand the various anti-forensics techniques it may leverage. Without doing so may result in an analyst missing something or reaching false conclusions. Plus, anti-forensics techniques provide details about malware functionality and can be used as indicators to find malware.

The week two readings continue exploring anti-forensics as well as self protecting strategies used by malware. The readings also go in-depth on Windows internals to explore covering items such as system architecture, registry, processes, and threads. All of the readings explore topics crucial for malware forensics and analysis.

Even though this is an online course I made a strong emphasis on the weekly labs so students explore processes, techniques, and tools. The week two lab ties together the week's other material by exploring how two malware samples use the Windows application programming interface to conceal data with different anti-forensic techniques.

The remaining weeks in the course ties together the material in a similar way I described for the second week. (There is more to the second week's material but I didn't think it was necessary to disclose every detail). The topics explored in the other weeks include but isn't limited to:

- Malware trends

- Malware characteristics

- Memory forensics

- Malware forensics

- Timeline analysis

- Static and dynamic malware analysis

The curriculum wouldn't be complete without requiring the students to complete work. In addition to weekly discussions about engaging topics there needs to be assignments to engage and challenge students. The assignments need to tie back to the course objectives and this was another area I made sure of. I'd rather not disclose the assignments I put together for the course or my thought process behind creating them. However, I will discuss one assignment that I think truly reflects the course; the final assignment. Students are provided with a memory image and a system forensic image and then are tasked with meeting certain objectives. Some of these objectives are: finding the malware, identifying the initial infection vector, analyzing any exploits, analyzing the malware, and conveying everything they did along with their findings in a digital forensic report.

In the end, the Malware Analysis course is just one of the courses in Champlain's MSDFS and certificate in digital forensic science programs; a course I would have killed to take in my collegiate career. A course with material that cannot be found in any training.

Developing the course has been one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences in my DFIR career. Not only did I develop this course but I'm also the instructor. One of the best experiences so far about my journey into academia has been watching the growth of students. Seeing students who never worked a malware case successfully find malware, identify the initial infection vector, analyze the malware, and then communicate their findings. Seeing students who already had DFIR experience become better at working a malware case and explaining everything in a well written report. My posts about academia may come to a close but the journey is only just beginning.

Why Academia Recap

My Journey into Academia post goes into detail about the issue where some academic programs are not preparing their students for a career in the digital forensic and incident response fields. How students coming out of these programs are unable "to analyze and evaluate DFIR problems to come up with solutions." In the words of Eric Huber in his post Ever Get The Feeling You’ve Been Cheated?:

"It’s not just undergraduate programs that are failing to produce good candidates. I have encountered legions of people with Masters Degrees in digital forensics who are “unfit for purpose” for entry level positions much less for positions that require a senior skill level."

As I said before, my choice was simple: to use my expertise and share my insight to improve curriculum; to put together a course to help students in their careers in the DFIR field.

Why Champlain College

Years ago I went to my first DFIR conference where I met Champlain's MSDFS program director at the time. One of the discussions we had was about the program being put together. A program that was supposed to not only help those looking to break into the field but to benefit those already in the field by covering advanced forensic topics.

Years later when an opportunity presented itself for me to develop the Malware Analysis course for Champlain's MSDFS program I remembered this discussion. I always heard great things about Champlain's programs and it was humbling to be offered this chance. It was even better when I took a look at the MSDFS curriculum. Seeing courses like: Operating System Analysis, Scripting for Digital Forensics, Incident Response and Network Forensics, Mobile Device Analysis, and then adding Malware Analysis to the mix. The curriculum looks solid covering a range of digital forensic topics; a program I could see myself associated with.

For those who don't want to pursue a Master's degree can have access to the same curriculum through their Certificates in Digital Forensic Science option. An option I learned about recently.

DFS540 - Malware Analysis Course

How can you reverse malware if you are unable to find it? How can you find malware without identifying what the initial infection vector is? How can you identify the initial infection vector without knowing what artifacts to look for? How can you consistently explore artifacts without a repeatable process to follow? How can you carry out a repeatable process with having the tools to do so? I could go on but this adequately reflects the thought process I went through when developing the curriculum. Basically, the course had to explore malware in the context that a DFIR practitioner will encounter it. To me, the best way to approach building the course was by starting with the course objectives and the following were the ones created (posted with permission):

- Evaluate the malware threat facing organizations and individuals

- Identify different types of malware and describe their capabilities including propagation and persistence mechanisms, payloads and defense strategies

- Categorize the different infection vectors used by malware to propagate

- Examine an operating system to determine if it has been compromised and evaluate the method of compromise

- Use static and dynamic techniques to analyze malware and determine its purpose and method of operation

- Write reports evaluating malware behavior, methods of compromise, purpose and method of operation

Course Textbooks

After the course objectives were created the next item I took into consideration was the reading materials. One common question people ask when discussing academic courses is what the courses’ textbooks are. I usually have mixed feelings about this question since the required readings always extend beyond textbooks. The Malware Analysis course is no different; the readings include white papers, articles, blogs, reports, and research papers. However, knowing the textbooks does provide a glimpse about a course so the ones I selected (as of the date this post was published) were:

Szor, P. (2005). The Art of Computer Virus Research and Defense. Upper Saddle River: Symantec Press.

Russinovich, M., Soloman, D., & Ionescu, A. (2012). Windows Internals, Part 1 (6th ed.). Redmond: Microsoft Press.

Honig, A, & Sikorski, M. (2012). Practical Malware Analysis: The Hands on Guide to Dissecting Malicious Software. San Francisco: No Starch Press.

Ligh, M., Adair, S., Hartstein, B., & Richard, M. (2011). Malware Analyst’s Cookbook and DVD: Tools and Techniques for Fighting Malicious Code. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing.

Course Curriculum

I started creating the curriculum after the objectives were all set, the readings were identified, and most of my research was completed (trust me, I did plenty of research). When building out the curriculum its helpful to know what format you want to use. Similar to my collegiate experience (both undergraduate and graduate), I selected the traditional teaching methods for the course such: lectures, readings, discussions, laboratories, and assignments. I made every effort to make sure the weekly material covered by each teaching method tied together as well as the material from each week.

Developing Weekly Content

To illustrate how the weekly material ties together I thought it would be useful to discuss one week in the course; the course's second week material which explores anti-forensics and Windows internals. Each week (eight in total) begins with a recorded lecture. The lectures either convey information that is not discussed in the readings - such as a process - or re-enforces the information found in the readings and lab. The week two lecture explores anti-forensics to include: what it is, its strategies, and its techniques to defeat post mortem analysis, live analysis, and executable analysis. When dealing with malware whether on a live system (including memory images), powered down system, or the malware itself it's critical to know and understand the various anti-forensics techniques it may leverage. Without doing so may result in an analyst missing something or reaching false conclusions. Plus, anti-forensics techniques provide details about malware functionality and can be used as indicators to find malware.

The week two readings continue exploring anti-forensics as well as self protecting strategies used by malware. The readings also go in-depth on Windows internals to explore covering items such as system architecture, registry, processes, and threads. All of the readings explore topics crucial for malware forensics and analysis.

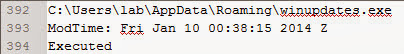

Even though this is an online course I made a strong emphasis on the weekly labs so students explore processes, techniques, and tools. The week two lab ties together the week's other material by exploring how two malware samples use the Windows application programming interface to conceal data with different anti-forensic techniques.

The remaining weeks in the course ties together the material in a similar way I described for the second week. (There is more to the second week's material but I didn't think it was necessary to disclose every detail). The topics explored in the other weeks include but isn't limited to:

- Malware trends

- Malware characteristics

- Memory forensics

- Malware forensics

- Timeline analysis

- Static and dynamic malware analysis

Assignments

The curriculum wouldn't be complete without requiring the students to complete work. In addition to weekly discussions about engaging topics there needs to be assignments to engage and challenge students. The assignments need to tie back to the course objectives and this was another area I made sure of. I'd rather not disclose the assignments I put together for the course or my thought process behind creating them. However, I will discuss one assignment that I think truly reflects the course; the final assignment. Students are provided with a memory image and a system forensic image and then are tasked with meeting certain objectives. Some of these objectives are: finding the malware, identifying the initial infection vector, analyzing any exploits, analyzing the malware, and conveying everything they did along with their findings in a digital forensic report.

Summary

In the end, the Malware Analysis course is just one of the courses in Champlain's MSDFS and certificate in digital forensic science programs; a course I would have killed to take in my collegiate career. A course with material that cannot be found in any training.

Developing the course has been one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences in my DFIR career. Not only did I develop this course but I'm also the instructor. One of the best experiences so far about my journey into academia has been watching the growth of students. Seeing students who never worked a malware case successfully find malware, identify the initial infection vector, analyze the malware, and then communicate their findings. Seeing students who already had DFIR experience become better at working a malware case and explaining everything in a well written report. My posts about academia may come to a close but the journey is only just beginning.

Labels:

education